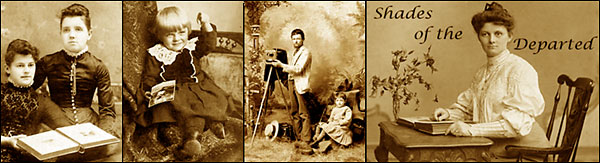

Twice Told Tuesday features a photography related article reprinted from

my collection of old photography books, magazines, and newspapers.

OLD PHOTOGRAPHS

The Living Age, 1913

One of the most envied accompaniments of high birth in the past is becoming almost universal. Almost everyone nowadays is possessed of family portraits. That is, they are possessed of accurate delineations of the features of their more immediate ancestors. Old photograph albums tell middle-aged men and women what their grandfathers were like before they grew old, and young people can study the clothes, faces, and deportment of their great-grandparents and great-aunts and great-uncles. We all have pictures of the block whence we were hewn—an advantage reserved at one time for chips of greater distinction. The fact ought not to be without its effect upon character—if the heirlooms of family tradition are of any value. As in the case of jewels, there is something fictitious about the store which is set by them. Nevertheless the fascination of such heirlooms is eternal

A really good collection of old family photographs is a great treasure. But why, as we turn over its pages, are we quite sure to laugh? What is there that is ridiculous about the earlier photographs? It is not very easy to say. They tell us truthfully a great deal about those who are separated from us by a small space of time and an immense expanse of change. The sitters are self-conscious. Some of their self-consciousness was doubtless due to the long exposure then necessarily exacted by the photographer, but also they are frankly trying to look their best. But whatever we may say of them as individuals, taken all together they bear witness to a simpler generation than ours.

It is curious how often they give an impression of belonging to a lower rank of life than the one they adorned. Any look of distinction is rare in an old photograph, and groups of children belonging to the well-off classes remind one of groups collected at a village school feast. To our eyes the men and the children of the early Victorian period were wonderfully badly dressed. Perhaps there has never been a period when the beauty of women was substantially injured by the fashions.; But if the men in early photographs lacked vanity to reform the tailoring art, they were not above striking an attitude in obedience perhaps to the suggestion of the photographer any more than their wives and daughters were. As we turn over the heavy leaves of the album we are sure to see a young soldier intending to look fierce, a young lady looking intentionally modest, a husband and wife exhibiting devotion by staring at one another, she from a chair that she may look up, he on his legs looking down. A clergyman, or perhaps he is only a grave father of a family, is represented with an enormous Bible on his knees, and a group of oddly dressed little girls are feigning interest in a geographical globe. We could not put ourselves into such self-conscious positions nowadays.

Would it be absurd to say that it is partly because we are too self-conscious? Reserve may become an affectation. A good deal of our vaunted simplicity arises from the terror we feel of being ridiculous. It la the simplicity of the schoolboy, who dare not be self-conscious and who is not in real truth a very simple being. No generation is a judge of Its own airs and graces. Will our photographs make our grandchildren laugh? Will they see an extraordinary egoism behind the studied simplicity of our attitudes and expressions?

Our grandfathers and grandmothers wished that their photographs should call attention to the fact that they were playing their parts well. Men and women in modern fashionable photographs say nothing about their roles. They call - attention - Loudly to their own individualities.

Will our descendants amuse themselves sometimes on Sunday afternoons comparing old "snapshots" with old fashionable photographs? Will they be so cruel as to believe that the snapshot was the more like? Probably not, because it is in the carefully taken photograph and not in the snapshot that family likenesses are most often obvious.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about old family photographs is the likeness we are able to trace between the representatives of one generation and another. At times, between fairly close relations, it approaches to something like identity. This impression is strengthened when we remember that likeness of feature almost always carries with it likeness of voice. For instance, we may find a very early Victorian lady in a crinoline, with banded hair. Her hand is upon the shoulder, perhaps, of a mild little boy in a species of fancy costume which was known as "kilts." The photographer desired to show the sedate tenderness of the early Victorian ideal matron, but the likeness to her great-niece strikes every beholder, and the great-niece is perhaps a suffragette.

Dressed like the photograph, supplied with the crinoline and a little boy, with rearranged hair and taking similarity of voice for granted, the two ladies would seem to be one. Would the aunt in the photograph have been a suffragette had circumstances permitted? Would the great-niece have been a mild, sedate lady of early Victorian proclivities under other conditions? We wonder perhaps what the great-aunt was really like. Probably no one can remember anything about her except that she lived in such-and-such a place, and that the boy died.

We turn to another picture, saying sadly that "there is no one now whom we could ask." There is no key now to the personality of the great-aunt except that of the great-niece who is so like her. It is sad how soon we are all forgotten, or remembered only by a resemblance which strikes beholders as ridiculous. "Quite comically like!" they cry as they look at the portrait. Change of circumstance does sometimes make a resemblance absurd. The prototype seems like the antitype masquerading, and It Is difficult to get away from the theatrical suggestion.

It is amazing what a likeness a large-headed, very untidily dressed young man in a photograph, who seems to be seeking a leonine effect, may bear to his young relation at Sandhurst. The modern military cadet, shocked by the much creased trousers, is perhaps the only person who does not see the likeness.

The early photographs of children seem at first as little like the children of to-day as the Fairchild family are like children in a modern story-book. All the same. If we isolate and magnify o rIngle face we may probably find Its antitype in the present nurseries of the family or at school. Old photographs of children are, however, very unsatisfactory. They are surprisingly without charm. Has the modern worship of children brought something out in them which was not patent in their little grandfathers? The painters contradict a theory to which early photography certainly lends a plausibility.

Why does the ordinary middle-class family beep so poor a record, not of its own doings—they are, for the most part, dull enough—but of its own personalities? None of us can see in front of us much further than the probable lifetime of our own children, and we do not like to look even so far as that.

Surely it would give us a sense of space if we could see clearly a little further behind us. Moreover, to those who are engaged in the bringing up of their own children, a history of the family might furnish many a hint. Would it not be a good plan if every family appointed a historiographer. It would be his or her duty to make a slight sketch in words of every living member of the family; to keep a few characteristic letters; to put down a few characteristic sayings, and to send this little dossier to some discreet person who should be agreed upon as a recipient of the family archives.

As a companion volume to the family album it would be very interesting! The post, too, would be an interesting one to fill. The choice would fall often, we think, upon an unmarried woman. Women are far more interested in character-study than men; unmarried women are apt to stand a little outside the family circle. Also such a woman would be likely to accept a somewhat onerous job for the sake of the sense that she was somehow augmenting the significance of her own blood, though only by words.

All the same, we are not sure but that the book might prove enervating reading. History repeats itself, as the photographs show us. A minute description of their forebears might remove from present members of a humdrum family all sense of originality, and leave them with a calm acquiescence in stagnation, a sense that there is nothing new under the sun, and that each successive generation is a reproduction of the last in different clothes and fresh circumstances.

"Old Photographs."

The Living Age, 1913.